Abraham Kuyper: his story

Abraham Kuyper: his story

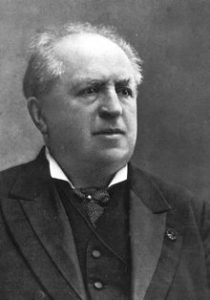

On November 8th 1920, Abraham Kuyper died. You may not have heard of him, but if you had lived in the Netherlands from about the 1880's to sometime after 1910, his would have been a household name. In his illustrious career he was a pastor and theologian, philosopher, journalist, founder of a university, prolific author, politician and reformer, and between 1901 and 1905 served as Prime Minister of Holland. His major lasting influence has been the way in which he explored the relevance of his deep Christian faith, rooted largely in Calvin’s understanding of the sovereignty of God, to every aspect of living in God’s world: art and science, education, culture and politics.

Abraham Kuyper was born in 1837 and received his education at Leyden, majoring in classics, philosophy and literature. In 1861 he married Johanna Schaay; they had eight children.1

Kuyper worked for a doctorate in theology which he received in 1863. In 1867 he was ordained to be pastor of a church in Utrecht, and in 1870 moved to another pastorate in Amsterdam. He was then part of the Dutch Reformed Church, the national church, which since the 1850’s had become increasingly modernist in theology, liberal and relativistic. However, by the 1870’s, there was a strong resurgence of conservative orthodox theology in some parts of the church, and in the 1880’s Kuyper became leader of the reformist group. Grieving the way the Dutch Reformed Church seemed to have lost its Reformed bearings, the breakaway group called themselves Doleantie(the grieving ones). By 1890, they had grown to more than 200 congregations. Eventually they joined with the Christian Reformed Church, which some decades earlier had separated from the state church, and together they formed a new denomination: Reformed Churches in the Netherlands, with Kuyper among its leaders.

From early in his adult life, Kuyper developed skills in journalism and for many years wrote a regular weekly newspaper column on Christian engagement on public affairs. In 1874 he stood for the Dutch Parliament and became an MP, which meant that though he continued as a lay church leader he could no longer remain an ordained minister. His life-long passion for justice, especially for the poorest and the most disadvantaged people, derived from his faith in the justice of God, fired his political endeavours. He was pastorally concerned especially for the children and young people who were growing up in poverty, many of whom were orphans. He got bills passed in Parliament to help them. He was also deeply exercised about the education system and worked hard on education reform. Though disagreeing with their theology, he cooperated significantly with Roman Catholics in Parliament, as part of what was called the Anti-Revolutionary Party - so called in opposition to the prevalent atheistic materialism which was believed to stem from the French Revolution. Indeed from 1888 until well into the C20th, it was the Reformed-Catholic coalition in the Dutch Parliament which made most of the running. From 1901 to 1905, Kuyper headed the Reformed-Catholic coalition in government as Prime Minister.

Kuyper’s own Christian faith was initially nurtured in a Calvinist upbringing, though when he became a student at Leyden, he ‘cast himself into the arms of barest radicalism’.2 He eventually found that this did not satisfy his mind, or warm his heart, and its ‘chilling atmosphere’ pushed him to search elsewhere. It was among the ‘simple people’, rural descendants of ‘ancient Calvinists’, and in particular spending much time in conversation with a devout ‘peasant women’, as well as reading Calvin’s Institutes, that he eventually found where he belonged. As Warfield commented: ‘It astonished him to find among these simple people a stability of thought, a unity of comprehensive insight, in fact a worldview’ which, for Kuyper, became the start of a ‘new enthusiasm of faith’, and his lifelong quest to explore the nature of theology and its implications for every sphere of life. One of the expressions of that quest was Kuyper's founding, with others, in 1880 of the Free University of Amsterdam, a Christian institution with faculties of arts, sciences, law, medicine and theology - and for a while Kuyper was the Rector, as well as a professor. One of the marks of his faith was his massive academic theological and philosophical work developing a neo-Calvinist world view, expressed in many publications, and in his public political activities. Another mark was that at the same time, he regularly published devotional meditations on the Scriptures. He wrote a series of meditations for his newspaper De Herautbetween October 1902 and January 1904, which were collected together as the first volume of To Be Near Unto God.

Abraham Kuyper seems to have been a remarkable leader and politician, a person of intelligence and great learning, of huge energy and zealous faith. He was bullish and determined, combative and defiant, and though he sought always to maintain close contact with ‘the common people’, he was probably not someone to get on with very easily at a personal level. The paradox of his life was well expressed by James Bratt in his magnificent biography3: “The Calvinist champion was a man of self-will; the man of faith, obsessed with working; the one humbled before God, yearning to be lifted high among men, and succeeding.”

Kuyper’s Primary Theological Emphases

What has come to be called Kuyper’s ‘neo-Calvinism’ provided him with two primary emphases in his developing worldview. The first was the sovereignty of God over all things: Jesus Christ is Lord of the universe, and therefore has authority over every aspect of life and culture. The second was the darkening of human understanding through sin. Sin’s ‘darkening’ means that in general we human beings, though made in God’s image, have broken our relationship with God, and have therefore also lost the coherence and integration of all things under God’s sovereignty. These two emphases give the context in which to understand Kuyper’s most often quoted saying, which has otherwise sometimes wrongly been construed as a bid for Christian imperialism, which was certainly not Kuyper’s view. It came in part of his inaugural lecture in the Free University of Amsterdam: ‘there is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry ‘Mine!’4 In other words, as Kuyper explains, Christ is both the personal Saviour of believing sinners who turn to him in faith, and through whom we can grasp again in our spirit something of the meaning of all things under God; and Christ is also Lord of the Universe and so sovereign over every sphere: art and science, education and culture and politics. Everything in the universe in some way expresses the revelation of God through Christ. The whole creation is like a curtain behind which we can sometimes glimpse the workings of God’s mind.

Being made in God’s image gives an equal value to every human life, and Kuyper recognises the rich and valued diversity of cultures and world-views (which led him to a progressive pluralism in politics). God has given to all human beings the mandate of responsible care for creation (Gen.1.27-8), which leads to the development of culture and civilisation. In Kuyper’s mind, as Bratt expounds him, this is seen as an ‘enduring command to humanity to develop the potential endowed in creation as service to God.’5 Christians have a particular responsibility to articulate what that must mean when, through the illumination of the Holy Spirit, they seek to acknowledge every aspect of life and culture as under the authority of Christ.

It is convenient to divide our exposition of Kuyper’s theological emphases into the four themes for which he is most often remembered: (i) ‘Palingenesia’; (ii) Common Grace; (iii). ‘Sphere Sovereignty’; (iv) The Work of the Holy Spirit. They are all part of Kuyper’s passion to awaken the church to a fresh awareness of Christ’s lordship over all things.

(i) ‘Palingenesia’

In 1898 Kuyper published a major three-volume heavyweight book entitled Encyclopedia of Sacred Theology: its principles. As we noted earlier, in his Introduction to that book, Warfield writes of Kuyper’s discovery ‘among these simple people’ of ‘a stability of thought, a unity of comprehensive insight, in fact a world-view’ which was the start of his new ‘enthusiasm of faith’. That world-view, says Warfield, was ‘based on principles which needed but a scientific treatment and interpretation to give them a place of equal significance over against the dominant [liberal] views of the age.’ So began Kuyper’s life-long quest to explore the nature of theology, and its implications for every sphere of life. The Encyclopedia of Sacred Theology is Kuyper’s attempt to present a modern Calvinistic world-view of strict scientific conception, comprehensive and detailed. In it, he explores the meanings of science, wisdom, faith and religion, and particularly the place of Christian theology in relationship to all the other academic disciplines. He examines the inspiration of the Holy Scriptures, theological method, and the history of theology.

In one major section of the EncyclopaediaKuyper argues that there is a fundamental distinction at the level of world-view between those who acknowledge the lordship of Christ over all things, and those who do not. This leads to two kinds of consciousness, and therefore to ‘two kinds of people’ and so ‘two kinds of science’. Kuyper’s starting point is the fact of sin, which darkens and impairs all knowledge, and must therefore impact our knowledge of God and of God’s world, and therefore our concept of truth. Kuyper builds on the Christian affirmations about ‘regeneration’, about being ‘begotten anew’ which, he says, ‘breaks humanity into two’. In Matthew 19.28 we find the Greek word ‘palingenesis’, sometimes translated ‘the new world’. It means new creation, starting over again. So there are ‘two kinds of people’.

This sort of language needs great care, as it all to easily leads to a 'them' and 'us' mentality: we are God's 'elect'; 'they are 'reprobate'. Such a distinction is not what Kuyper meant. The 'antithesis' is not between identifiable Christian or non-Christian groups, but rather between two fundamental spiritual principles which cut through all groups and all people. Thus, all people are human, made in God’s image, dependent on God for life and the means of life, but some live within a world rooted in secular materialism, whereas others live within a ‘new world’ in which all things and all people are understood to depend on the Creator God, and seek to live under God’s lordship in all things. ‘Palingenesia’ is not only about the renewal and redemption of individual people through the grace of Jesus Christ - though it crucially includes that - but about the renewal and redemption of the whole universe. Where the secular world, based on naturalistic evolution, looks for ‘progress’, the Christian world, says Kuyper (who was very sympathetic to a theistic evolution), looks for ‘cosmic regeneration’ by God’s Spirit.

Kuyper does not mean that there is any difference in the actual doing of science, but that the fundamental assumptions about the world, which affect the motivations of scientists, are essentially different. ‘Whether a thing weighs two milligrams or three, can be absolutely ascertained by everyone that can weigh.’6 But different starting points can lead to different conclusions – and this is especially true when we look at the ‘spiritual’ or ‘psychological’ sciences, including history and economics. Different basic assumptions often lead to different conclusions – those who take their starting point in the spirit of the world may see thing differently from those whose starting point is the Spirit of God. Christian people themselves can be led astray, and need constantly to be brought back to their starting point in the Spirit of God. One of the implications of Kuyper's doctrine is the need for a proper understanding of 'commonness' - what is it that unites us as human beings made in God's image, both believers in Christ and non-believers?

All these points Kuyper elaborates in painstaking detail which makes heavy demands on the reader. His primary point is clear: “It is time we broaden our spiritual horizon and recognise that Jesus as King has sovereignty over the totality of human culture. Once that is realised, it becomes inevitable that both our spiritual development unto eternal life and our general cultural development, that has led to such an amazing increase in our knowledge and control over nature, are placed under his rule.”7

(ii) Common Grace

As with Calvin, the whole of Kuyper’s theology is an exposition of God’s grace. There is a special, redeeming grace – the grace of new creation - which transforms a person’s sinful nature, and so illuminates that person with God’s Spirit that they renounce unbelief and instead seek to serve God in obedience to God’s will. And there is also, he argues, a commongrace which restrains the tendency of all fallen humanity towards ungodliness, and instead encourages all people towards actions that are beneficial to the human race as a whole, and which further the common good. Common grace is the means by which God’s intention that the human race should flourish as a community of willing service to the glory of God should not be thwarted by our fall into sinfulness. Wherever there is action towards health, goodness, justice, and the common good – there is common grace. Both aspects of grace are loving gifts from God.

This theology was not without its critics. Kuyper’s theology of common grace was sometimes interpreted as leading to an emphasis on creation and culture at the expense ofevangelical doctrines of the need for personal salvation. Indeed, in the 1920's there was a large split within the Christian Reformed Church in the USA between those who sided with Kuyper's understanding of common grace, and others who argued that Calvin never taught such a doctrine, and that indeed all who are without the saving grace of Christ remain under God's wrath and judgement of condemnation. To be sure, Calvin does not use the term 'common grace', but he says much about the providence, kindness, mercy and compassion of God for all sorts of people, in an inclusive way which Kuyper follows. Kuyper did indeed stress personal redemption, but in the context of a cosmic redemption, also gained by Christ at the cross. Kuyper's celebration of the whole of God’s creation did not focus on this earth to the exclusion of supernatural things (as some critics maintained). Creation was seen rather as God’s handiwork through which God’s own life and attributes are revealed. God’s kingdom comes ‘on earth as it is in heaven’. And Kuyper emphasises that ‘The Church forsakes its principles when it is concerned only with heaven and does not relieve earthly need.’8

Kuyper rejected the medieval theological distinction between nature and grace, and instead saw all spheres of life as subject to the laws of God. Common grace is God’s gift to hold back the darkness of sin, to restrain the effects of the Fall, to sustain and preserve and heal the created order, and provide a context in which all human talents can flourish for the good of all. His theology was, therefore, a very strong endorsement of the doctrine of creation, and the celebration of the whole of God’s created order in its potentialities and gifts, and therefore a celebration of every culture and civilisation.

A translation of Kuyper’s major multi-volume work on Common Grace is still being made, but sections are available in English, notably Wisdom and Wonder, which focusses on science (which we have already noted), and on art, of which Kuyper says that all the arts should seek to glorify God, but sin which has darkened our minds has also distorted our senses, though through God’s common grace, a light of beauty can still shine through. Common grace is also a theme of Kuyper’s hugely significant work, published as Lectures on Calvinism. This is the text of the Stone Lectures which Kuyper gave in Princeton in 1898. They included lectures on Kuyper’s views on ‘Calvinism’ (his word for the Christian ‘life-system’ or ‘world-view’ derived from Calvin’s theology of the sovereignty of God). He began with a note of caution: this world-view, Kuyper argued, was in ‘mortal combat’ with the sort of ‘modernism’ which builds a world of its own without reference to God. It was this faith in which ‘my heart has found rest. From Calvinism I have drawn the inspiration firmly and resolutely to take my stand in the thick of this great conflict of principles… Calvinism , as the only decisive, lawful and consistent defence for Protestant nations against encroaching and overwhelming Modernism.’9

So Kuyper explores the significance of ‘Calvinism’ as a ‘life-system’ (or what James Orr called 'world-view'); Calvinism and Religion, and Politics, and Science, and Art. He ends (this is 1898) with ‘Calvinism and the Future’ in which he argues that ‘Calvinism did not stop at church-order, but expanded in a life-system, and did not exhaust its energy in a dogmatical construction, but created a life- and world-viewand such a one as was, and still is, able to fit itself to the needs of every stage of human development, in every department of life’.

These Princeton Lectures established Kuyper’s reputation in the American Church, and his work continues to be studied among many American Christians, especially those of the Christian Reformed Church. His work influenced Francis Schaeffer, the founder of L’Abri Fellowship, and is quoted and discussed in the widely used text Faith and Rationalityedited by Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff.10

One major question this raises for contemporary thinking is the extent to which we can still speak meaningfully - as Calvinists (and those who like Kuyper wish to bring Calvinism up to date) wish to - of human solidarity and shared rationality under God, in a post-modern culture which rejects commonality; relativises rationalities; celebrates fragmentation.11

(iii) Sphere Sovereignty

When Kuyper writes of ‘every sphere’ of life being brought under the lordship of Christ, he is picturing human society as a collection of spheres of different associations in which different functions of human life are allowed to develop freely in accordance with their own purposes, and not under the control of another. So one sphere – the State – cannot have control over another sphere – the Church; likewise the Church may not dictate to the State. The State may not claim authority over science, or the arts. Every ‘sphere’ (in which Kuyper includes not only Church and State and science and art, but also education, ‘civil society’, the family and others) has its own autonomy, even its own derived sovereignty under the lordship of Christ and the supreme sovereignty of God. The State, and its leaders, is accountable to God for the exercise of lawful power in the pursuit of common justice. The Church is accountable to Christ its Head. Science is answerable not to political convenience but to the sovereignty of God's truth.

So each sphere of human life, the personal, the social, the ecclesial, the economic, the household; the worlds of science and politics, are separate and, dependent on God, are free to develop in their own ways for the flourishing of all humanity and ultimately for the glory of God. They are also ‘organically’ related to each other within the nation as different and complementary expressions of the unfolding of human nature in history.

It is on the ground of ‘sphere sovereignty’ under the sovereignty of God that Kuyper developed his own personal political viewpoint: very conservative in some respects and very liberal in others. He said he despised what he called ‘socialism’ (by which he mostly meant what many today call ‘statism’12) because of its avowed atheistic materialism, and especially because it refused to recognise any authority other than its own. He would have little time either for today’s ‘statism’ – the totalitarian demands of political authority, or for today’s corporate capitalist power which seems to operate without any accountability. As Jonathan Chaplin wrote: “Kuyper’s vision can be an inspiration for Christians today facing the double threat of exploitative capitalism and overweening statism – both deeply secularising forces.” Chaplin is referring to Kuyper’s critique of ‘secularism’, which is also a critique of how secular political ideologies of right and left, violate the ‘sphere sovereignty’ of civil society institutions.

Chaplin also underlined Kuyper’s defence of an equitable pluralism of worldviews in the public sphere. ‘His aim for Christians in the public realm was not to seek a position of privilege, but to enjoy equal rights alongside other ‘confessional communities’, both religious and secular, within a constitutional democracy marked by wide freedom of expression, fair representation, and a diversity of voices. “our unremitting goal should be to demand justice for all, justice for every life expression.”

This was a celebration of diversity and of political pluralism under God.

‘Christians, and not only those in the Reformed tradition’ Chaplin writes, ‘owe a great debt to Kuyper for laying out what was probably the most compelling defence of pluralism in the nineteenth century, anywhere…. What Kuyper uniquely offered… was a rare lesson in how to realise three goals simultaneously: the nesting of a commitment to pluralism within a comprehensive social and political theory grounded in biblical Christianity; the launching of a successful political movement to implement that commitment in the teeth of a powerful secularising Liberal establishment; and the utilising of the platform thereby created to establish common ground with his opponents and to contribute to the common good of the nation.’

Kuyper was happy to describe himself as a Christian democrat. His had a deep concern for the alleviation of poverty and the removal of injustice. He believed that in its own sphere, the State has a duty to promote welfare and health, social security and workers’ rights. He always wanted to press for the fullness of human life and the celebration of the whole of God’s creation. Kuyper’s approach was primarily to seek reformation through journalism, education and political action. He constantly sought to hold the political tension between liberation and order. He sought to capture the sense of divine coherence in all things. His major political motivation was captured in the title of his own newspaper: ‘Justice for all’.

(iv) The Work of The Holy Spirit

In a sense, everything that Kuyper has written bears on the great theme of God’s Spirit, and the illumination of the Holy Spirit in our spirits which enables us to explore the Wisdom of God’s mind, and try to find a language in which to express something of that. It was in the year before he became Prime Minister that Kuyper’s major book The Work of the Holy Spirit was published (1900). This magisterial treatment has become a theological classic. Kuyper covers the role of the Holy Spirit both in creation and in redemption, in illuminating the Scriptures, in the mystery of the incarnation and in the mediation of Christ, in regeneration, repentance, faith, sanctification and love and prayer, and in the life of the Church as the Christ’s Body. Kuyper brings clearly together the themes of both cosmic renewal and personal salvation through the work of the Spirit, the Giver of Life.

If God the Father is the fountainhead of the ‘materials, forces and plans’ of the universe, and God the Son through Wisdom and Word is the ordering power, giving meaning and consistency to all things and holding all things together, the life-giving Holy Spirit is the working of God bringing all things to their perfection and to their true destiny.

“The creature is made not simply to exist, or to adorn some niche in the universe like a statue. Rather was everything created with a purpose and a destiny; and our creation will be complete only when we have become what God designed. Hence Gen.2.3 says 'God rested from all his work which he had created to make it perfect.' (Dutch translation). Thus to lead the creature to its destiny, to cause it to develop according to its nature, to make it perfect, is the proper work of the Holy Spirit.”13

Kuyper speaks of the Holy Spirit dwelling in our hearts, energising our actions and inspiring our prayers. Alongside his regular journalistic political column, Kuyper also wrote daily meditations on Christian prayer and spirituality, eventually published as To Be Near Unto God.In fact most of his writings have a devotional character, and his own spiritual life was sometimes described as mystical. Kuyper thought of thinking as a spiritual activity. For him all of life was ‘religious’, though not all life was ecclesiastical! Like Calvin’s, Kuyper’s theology was geared to the knowledge and obedience of God, illuminated, inspired and energised by the Holy Spirit. He insisted that knowing God can only be learned by doing. To grow in holiness is the Christian’s calling, and it is a lifelong struggle against temptation. It is fitting to include a quotation which is a small part of one of his mediations from To Be Near Unto God. It is easy to forget that these words are written by a national political leader who had been Prime Minister:

‘In the light of God’s countenance you learn to know God. When this beams forth, His Spirit emerges from its hiding and approaches your soul in order to make you see, perceive and feel what your God is to you. Not in any doctrinal form, not in a point of creed, but in outpourings of the Spirit of unnameable grace and compassion, of an overwhelming love and tenderness, of a Divine pity which enters every wound of your soul and anoints it with holy balm’.14

Kuyper today

Despite his many acknowledged faults and short-comings, Kuyper’s wide vision, deep spirituality and the practical outworking of his faith can still be an inspiration for the Christian church today. His passion was always to ‘awaken the church to a fresh awareness of Christ’s lordship over all things’. And his bold determination to push to the limit the implications of a Christian world-view, and search out what it means to say that Christ is Lord of all in relation to every sphere of life, is a message which he brought to the increasingly secular and materialist world of his day, and is no less pertinent today.

We may be especially grateful for the following:

- Kuyper’s insistence that all things are held together and have their meaning under the sovereignty of God that led to his celebrating the value, dignity and gifts of every individual person made in God’s image. It led to his delight in and celebration of science, art, and all culture. It led to an understanding of the organic nature of society, of mutual interdependence, of healthy political pluralism. What would Kuyper make today of our western obsession with economic growth and the Free Market? I think he would argue instead for an economic model related to human advancement and the flourishing of the whole environment.

- Kuyper's celebration of God’s creation was seen in his promotion of every aspect of human creativity and knowledge, in art and science as in education and other aspects of human cultures. Seeing 'nature' as God's gift, and that all we have, life and the means of life come to us as gift, inspires an approach to responsible care of God's creation. What would Kuyper today encourage us to do in relation to loss of biodiversity, environmental degradation and climate change?

- Kuyper's rejection of the divide between nature and grace and his teaching on God's common grace that elevated every aspect of life to the realm of the sacred. Kuyper's doctrine enabled him enthusiastically to celebrate all that is good, health-giving, beautiful and true, wherever he finds it.

- Kuyper's understanding of common grace inspired his quest for justice in all human affairs. It upheld the tensions between liberty and order, and the promotion of equality, pluralism and diversity and inclusion in human societies and communities. Common grace was the motivating factor for Kuyper's approach to public theology. How would Kuyper today respond to the growing inequalities within societies, and between the developed and less-developed world?

- Kuper's understanding of sin as the darkening of the mind and the numbing of the senses that inspired his evangelistic zeal in preaching about the vital and life-giving illumination of God’s Spirit in our spirits, and the huge importance of ‘new birth; new creation’ as God’s gift to renew and regenerate both individual people, and the whole of a fallen world. How do we translate Kuyper's understanding of cosmic redemption into today's mission and today's hope?

- Kuyper's celebration of the work of God's Spirit, not only in bring people to 'new birth', but as the indwelling, life-giving and sustaining power of all life, creating 'space' for all of life to unfold, led him to share St. Paul's view that all things are held together in Christ,15 and to see the Spirit as the God who brings all things to their fulfilment.

In Kuyper, who always knew himself to be a sinner in need of grace, we see a man who in all the struggles, disappointments, set-backs and trials of his life, determined to hold the material and the mystical together; the mind and heart; earth and heaven. His passion was for individual people should come ‘near unto God’ – in the context of the whole of creation and human culture being redeemed in Christ. His life was one long journey of working out the implications of his fundamental belief: that over every square inch of this universe, Jesus Christ is Lord.

Bibliography

Abraham Kuiper

Encyclopedia of Sacred Theology: its principles. New York: Scribners 1898.

Wisdom and Wonder: Common Grace in Science and Art. Grand Rapids: Christian’s Library Press 2011.

Lectures on Calvinism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1975, being the Stone Lectures given at Princeton in 1989.

The Work of the Holy Spirit. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1975; first published 1900.

To Be Near Unto God. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1925.

James D. Bratt. Abraham Kuyper, Modern Calvinist, Christian Democrat. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 2013.

James E. McGoldrick.Abraham Kuyper, God’s Renaissance Man. Darlington: Evangelical Press, 2000.

Jonathan Chaplin. "The Full Weight of our Convictions: the Point of Kuyperian Pluralism",Comment, 1 November 2013.

Vincent Bacote. The Spirit in Public Theology. Eugene Oregon: Wipf and Stock, 2010.

Peter Heslam. Creating a Christian Worldview. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1998.

Richard J. Mouw. He Shines in all that's Fair: Culture and Common Grace. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001.

Footnotes

1. Herman, their first child, was born in 1864, and died in 1945; Catharina (number 6) lived longest into the C20th and died in 1955.↩

2. References in this paragraph are from Benjamin B Warfield’s introductory essay to Encyclopaedia of Sacred Theology.↩

3. Bratt, p. 375.↩

4. From a translation of the speech, quoted in McGoldrick, p.62.↩

5. Bratt, p. 194.↩

6. Encyclopedia.↩

7. Quoted in McGoldrick p. 147.↩

8. Quoted by McGoldrick p. 83.↩

9. Lectures on Calvinism p. 12.↩

10. Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff eds. Faith and Rationality: Reason and Belief in God, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1983, many reprintings. The work of Plantinga and Wolterstorff represents the strand of Christian philosophy known as ‘reformed Epistemology’. Kuyper also significantly influenced two other strands of philosophy, those associated particularly with Cornelius Van Til, and those linked with the work of Herman Dooyeweerd. ↩

11. cf. Richard Mouw p. 12.↩

12. What Kuyper has in mind here is late 19th European, especially German and French, socialism. Or, ‘Social Democracy’, which in that context meant a revisionist version of Marxism.↩

13. The Work of the Holy Spirit. p. 21.↩

14. To be Near Unto God: section 20.↩

15. cf. Col. 1.15 - 20.↩

Dr David Atkinson is a former Bishop of Thetford